Clinical Problem

Accidents are the leading cause of death in the age group up to 40 years, significantly outranking other prevalent conditions such as cardiovascular disease or cancer. [1] Every year, between 5.500 and 5.800 individuals lose their lives in the Netherlands as a consequence of accidents or violent acts. In emergency departments (EDs), around 900.000 patients are treated, with 150.000 requiring hospitalisation yearly. Abdominal trauma is present in 7-10% of all trauma victims, with the liver and the spleen being the most common injured organs with a prevalence of 36% and 32% respectively. [2] Their relatively large size, position in the intraperitoneal cavity, and abundant vascular supply make them susceptible to damage and potential sources of catastrophic bleeding. [3]

Initial trauma assessment is a fast-paced and challenging activity, which is unlike most other clinical activities. A multidisciplinary team performs multiple evaluations and procedures simultaneously during the initial trauma assessment. Many critical decisions are made. Along with cognitive bias of the members of the team, typical circumstances may also hamper diagnostic performance. [4, 5] Unstable patients, incomplete or absent relevant clinical information, mental and physical fatigue, and excessive workloads that shorten the time spent on examinations create an environment that is prone to medical errors. In fact, diagnostic errors are more likely to occur in the emergency department than anywhere else.[6] A timely diagnosis of injuries and prompt initiation of appropriate care is mandatory to prevent further harm at a later point in time. The major challenge Emergency Departments (ED) face when treating trauma patients involves diagnosing life-threatening injuries and initiating appropriate treatment without delay. [7]

The use of contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) is currently the gold standard for the diagnosis of hepatic and splenic injuries following trauma. [8] According to the results of the CT scan, together with the physiological status and the expected course, the trauma team will determine whether an intervention is needed. An early detection of injuries is vital in order to provide the patient with the appropriate monitoring and treatment. Identifying injuries early may prevent late complications, which may result in mortality and morbidity. [9] Still, reporting a trauma evaluation can be a challenging task, even for the most experienced radiologists. When multiple injuries are present, the staff may become distracted by the most obvious or major injury and overlook others.

Detecting trauma injuries from imaging has great importance in providing the best care to the patient. In this work, we propose a Deep Learning method, based on a small dataset, can detect and segment injuries to assist the trauma team in the early detection of injuries.

Data

The dataset contains patients sixteen years of age and older who sustained a high energetic trauma (HET) between 2015 and 2021. The study identified patients who underwent a primary survey and CT scan of the abdomen within 24 hours of the trauma. In addition to the initial selection of patients, an additional exclusion criteria was applied based on the quality of the scans. This study excluded any scans with partial or absent liver or spleen regions, insufficient quality, incorrect scanner contrast phase, or files not retrievable from the hospital’s database. In order to assess the extent of damage to the body, patients in the ER may undergo a full-body scan or an abdominal scan. Accordingly, the data compiled contained 51 patients who had sustained liver injuries and 52 patients who had sustained spleen injuries. Of these patients, 7 suffered a vascular injury to the liver and 16 to the spleen. Segmentation labels were produced for the following classes: liver healthy parenchyma, spleen healthy parenchyma, liver damaged parenchyma, spleen damaged parenchyma, liver vascular injury, and spleen vascular injury. A reader study was performed to validate the dataset.

Method

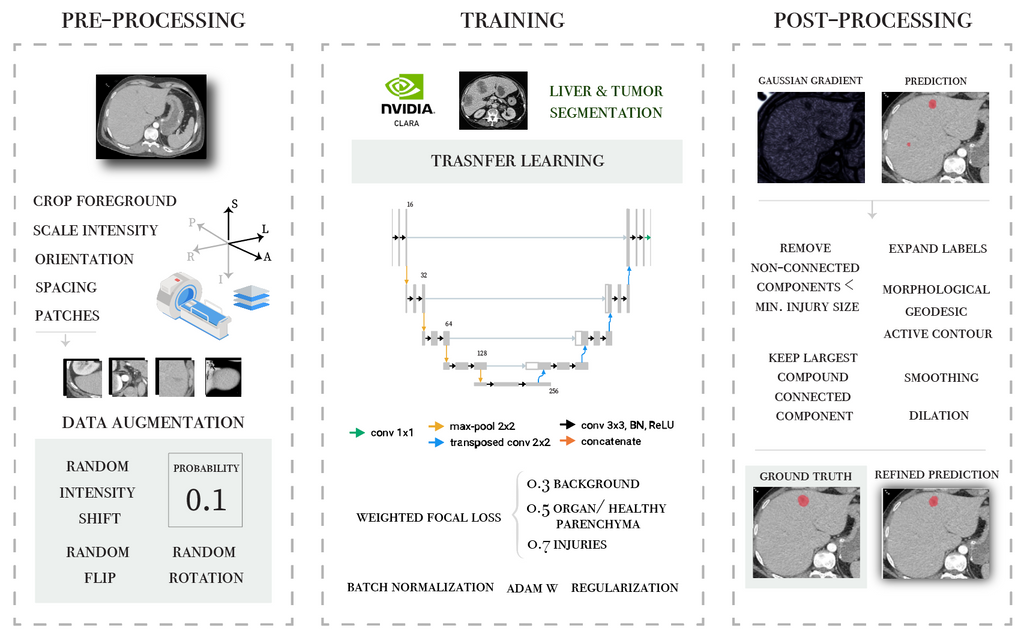

Two different methods were evaluated in this project. First transfer learning techniques were applied for the segmentation of hepatic parenchymal injuries. An overview of the pipeline is presented in the following diagram.

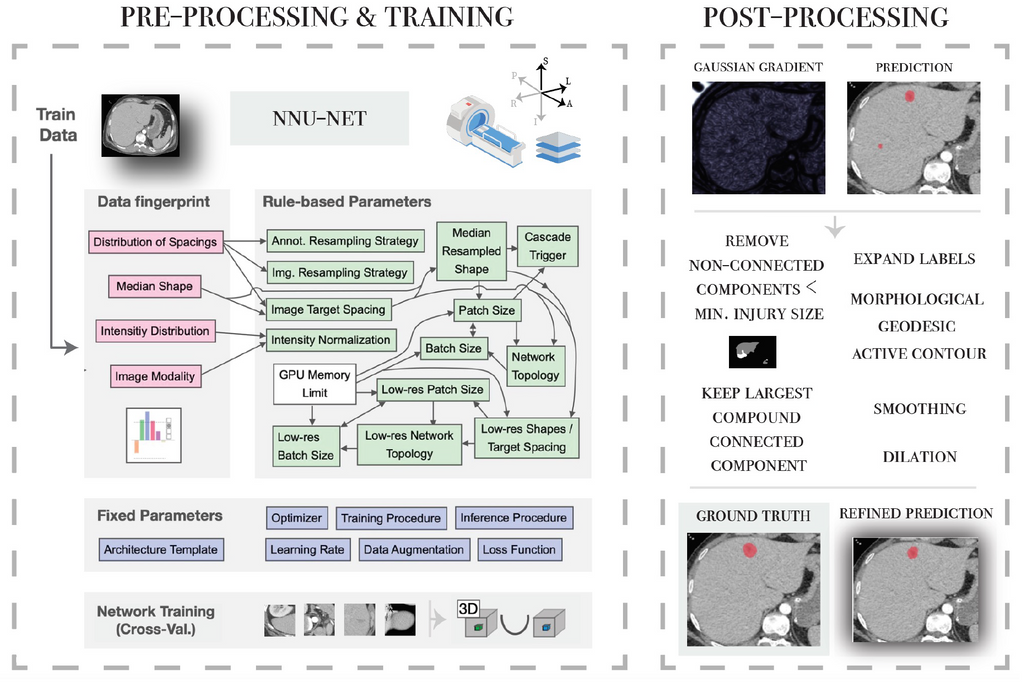

Secondly, the nnU-Net framework is applied for 3 different tasks: the segmentation of parenchymal and vascular injuries in the liver and spleen. A personalised post-processing based on domain knowledge is incorporated in the workflow.

Results

The results are presented in the tables, including the values for each metric evaluated, followed by the standard deviation. All injuries were correctly identified by both the Transfer Learning model

and the nnU-Net model. The nnU-Net model, in conjunction

with our domain-based post-processing method, produced the best scores for the injuries, resulting in a dice score of 0.75.

| Liver Healthy Parenchyma | Liver Injured parenchyma | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dice Score | Jaccard | Precision | Recall | Dice Score | Jaccard | Precision | |

| Unet (Transfer Learning) | 0.91 ± 0.07 | 0.83 ± 0.11 | 0.94 ± 0.05 | 0.88 ± 0.11 | 0.63 ± 0.24 | 0.49 ± 0.25 | 0.59 ± 0.28 |

| nnunet | 0.94 ± 0.06 | 0.90 ± 0.09 | 0.93 ± 0.08 | 0.96 ± 0.03 | 0.72 ± 0.17 | 0.59 ± 0.19 | 0.77 ± 0.25 |

| nnunet & post-processing | 0.93 ± 0.06 | 0.87 ± 0.09 | 0.93 ± 0.08 | 0.93 ± 0.06 | 0.75 ± 0.13 | 0.61 ± 0.16 | 0.78 ± 0.15 |

Similarly, the segmentation model for splenic injuries produced comparable results. However, generalizing the this task appears to be a greater challenge. The dice score was improved by 0.05 after applying the post-processing.

| Spleen Healthy Parenchyma | Spleen Injured Parenchyma | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dice Score | Jaccard | Precision | Recall | Dice Score | Jaccard | Precision | Recall | |

| nnunet | 0.90 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.37 | 0.89 ± 0.07 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | 0.63 ± 0.22 | 0.49 ± 0.24 | 0.78 ± 0.12 | 0.60 ± 0.27 |

| nnunet & post-processing | 0.90 ± 0.05 | 0.83 ± 0.08 | 0.90 ± 0.06 | 0.92 ± 0.06 | 0.68 ± 0.11 | 0.51 ± 0.12 | 0.67 ± 0.15 | 0.70 ± 0.20 |

The best segmentation models for each of the organs were further evaluated on a dataset consisting of 60 scanners collected from trauma patients who did not sustain abdominal injuries. This evaluation assesses the model as a classification problem rather than a segmentation problem. Its purpose is to analyze the likelihood of the model producing false positives (i.e. detecting injuries when none are present). In light of the imbalance between classes, the precision, recall, and f1 scores were presented as a weighted average based on the support of each class. For the liver, the model had a recall of 0.86, a precision of 0.94, and a f1 score of 0.88. For the spleen, the model had a recall of 0.84, a precision of 0.91, and a f1 score of 0.86. In most cases, false positives can be attributed to artefacts in the image or low attenuation areas near (or caused by) anatomical variations in the organs of interest.

Given the limited number of patients that suffer from vascular injuries, the segmentation model of splenic vascular injuries was tested on three injured patients. Table 5.4 presents the results. The model could detect all vascular injuries from the three cases evaluated, with an average segmentation dice score of 0.6. The precision of the model was 0.67, which implies that it is capable of retrieving most of the pixels labelled as vascular injury.

| Splenic Vascular Injuries | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dice Score | Jaccard | Precision | Recall | |

| nnunet | 0.61 ± 0.22 | 0.47 ± 0.22 | 0.59 ± 0.26 | 0.67 ± 0.20 |

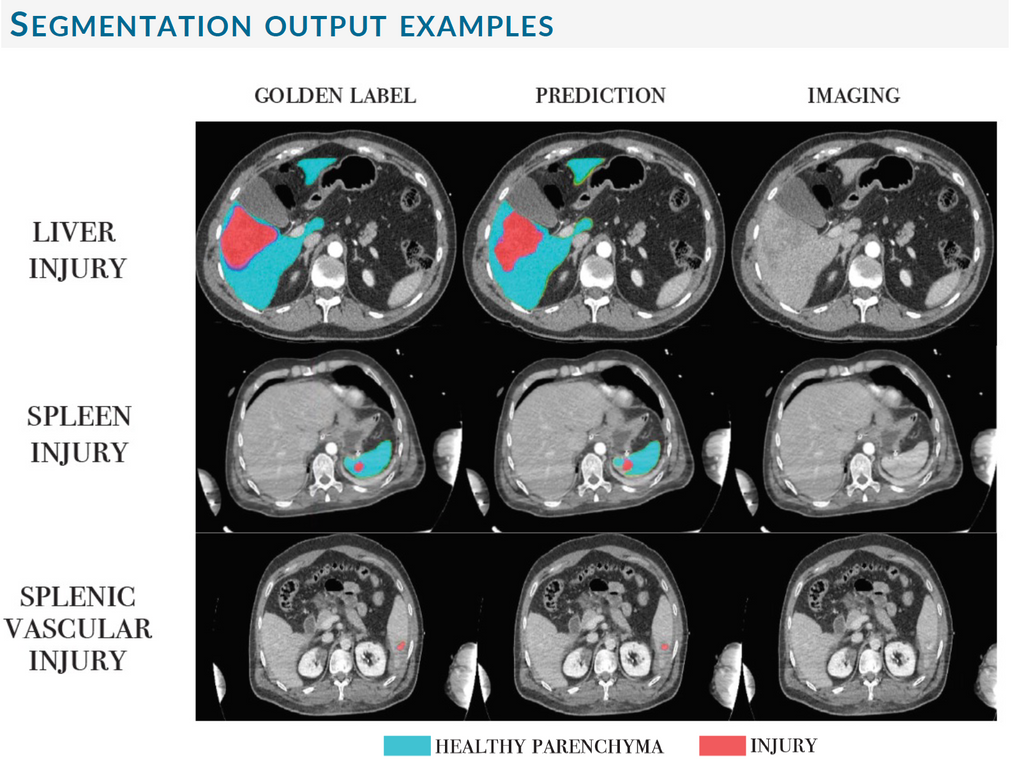

The following figure illustrates segmentation examples of the best models for each of the tasks.

Conclusions

The segmentation of abdominal trauma injuries is a novel and challenging task with enormous potential to improve the care of patients in the emergency room. Due to their ability to extract relevant features and patterns from data, deep learning methods have gained considerable attention in the detection and segmentation of medical images. Our study proposes and evaluates two segmentation U-net based models to detect liver and spleen injuries automatically. According to our study, we conclude:

-

Transfer learning from medical images shows promising capabilities to fasten and improve the learning process of segmentation tasks. In particular, transfer learning from liver tumours appears to be especially successful for liver trauma injuries due to the similarity of the two tasks.

-

The nnU-Net framework delivers exceptional results for the segmentation of healthy and injured parenchyma, regardless of the grade of injury. In addition, tailored post-processing based on domain knowledge improves this performance even further.

-

Even with a very limited dataset, consisting of no more than 13 training samples, the deep learning model was capable of detecting and segmenting vascular injuries. This is a ground-breakingfinding. It is imperative to treat vascular injuries as soon as possible. Bringing these models to emergency rooms could prove extremely useful towards assisting physicians in identifying such injuries. Thus reducing mortality and morbidity in trauma patients.

Link to GC

Try out the liver trauma injuries algorithm

Try out the spleen trauma injuries algorithm

Try out the spleen vascular injuries algorithm

Link to Code

The code for this project can be found in this GitHub repository.

References

[1] N. V. voor Traumachirurgie, “Verkeersongevallen | nederlandse vereniging voor traumachirurgie,”

[2] A. El-Menyar, A. Parchani, R. Peralta, A. Zarour, H. Al-Thani, A. Al-Hassani, H. Abdelrahman, and S. Arumugam, “Frequency, causes and pattern of abdominal trauma: A 4-year descriptive analysis,” Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock, vol. 8, p. 193, 10 2015.

[3] M. O. Malaki and K. Mangat, “Hepatic and splenic trauma,” http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1460408611400972, vol. 13, pp. 233–244, 7 2011.

[4] L. L. Leape, “Error in medicine,” JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association,vol. 272, p. 1851, 12 1994.

[5] S. Waite, J. Scott, B. Gale, T. Fuchs, S. Kolla, and D. Reede, “Interpretive error in radiology,” AJR. American journal of roentgenology, vol. 208, pp. 739–749, 4 2017.

[6] N. Sevdalis, R. Jacklin, S. Arora, C. A. Vincent, and R. G. Thomson, “Diagnostic error in a national incident reporting system in the uk,” Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, vol. 16, pp. 1276–1281, 12 2010.

[7] L. L. Geyer, M. Körner, U. Linsenmaier, S. Huber-Wagner, K. G. Kanz, M. F. Reiser, and S. Wirth, “Incidence of delayed and missed diagnoses in whole-body multidetector ct in patients with multiple injuries after trauma,” Acta radiologica (Stockholm, Sweden : 1987), vol. 54, pp. 592–598, 6 2013.

[8] W. Yoon, Y. Y. Jeong, J. K. Kim, J. J. Seo, H. S. Lim, S. S. Shin, J. C. Kim, S. W. Jeong, J. G. Park, and H. K. Kang, “Ct in blunt liver trauma.,” Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc, vol. 25, pp. 87–104, 1 2005.

[9] R. L. Gruen, G. J. Jurkovich, L. K. McIntyre, H. M. Foy, and R. V. Maier, “Patterns of errorscontributing to trauma mortality: Lessons learned from 2594 deaths,” Annals of Surgery, vol. 244, pp. 371–378, 9 2006.