Start date: 01-03-2020

End date: 31-08-2020

Clinical problem

Muscle ultrasound is a useful and patient friendly tool in the diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected neuromuscular diseases. These diseases can affect the muscles and the nerves that connect them and an early and reliable screening method can ensure early targeted patient care. Generally, they cause structural changes such as fibrosis and fatty infiltration that increases muscle echogenicity (i.e. how bright the muscle appears in an ultrasound image). A quantitative method developed at RadboudUMC extracts the echogenicity of the muscle tissue from ultrasound images and aggregates the value from multiple muscles using rules to screen for neuromuscular disease. This method has been proven to be more reliable and more sensitive in detecting neuromuscular diseases than visual evaluation, with a sensitivity of 92% in a homogenous population of children suspected of NMD. However, widespread implementation of the method is currently out of reach: The same muscle imaged on two ultrasound devices of different types will not show the same echogenicity. This is due to differences in beam-forming, post-processing of the raw radio frequency signals and physical characteristics of the acoustic array. Furthermore, the post-processing is machine specific, affecting the echogenicity even more. As a consequence, the reference echogenicity values that need to obtained in a time-consuming and expensive manner by sampling healthy volunteers do not transfer between different devices. Consequently, the sampling process is required for each new device type that is to be used. This fact is a major impediment to wider adoption of neuromuscular ultrasound by other hospitals.

Solution

The goal of this project was to develop a new device-independent method that can discriminate between muscle ultrasound images from healthy subjects and patients with a neuromuscular disease.

Tasks

To date, the only parameter clinically validated to discriminate between healthy and diseased muscle ultrasound images is its echogenicity (gray value). Probably, other features than echogenicity can be extracted from the muscle ultrasound images that discriminate between healthy and diseased muscle. The AI challenge in this project was to develop an algorithm that can extract these features from muscle ultrasound images that is independent from the ultrasound machine. Specifically, the task for this project was to develop an AI algorithm that 1) can classify patients with a neuromuscular disease based on a set of muscle ultrasound images, and 2) can perform this classification on ultrasound images from different ultrasound machines and setups.

Innovation

Since 2002, the clinical neurophysiology laboratory of the department of Neurology at the Radboudumc performs research on the frontier of neuromuscular ultrasound. The technique of quantitative muscle ultrasound based on echogenicity has been developed in our lab and is part of our routine daily clinical practice. However, a new method to screen for neuromuscular diseases based on ultrasound images that is device independent is much needed to able to continue this routine care when our current ultrasound machine is eventually phased out. Thus, if a reliable AI algorithm can be developed to screen for neuromuscular disorders this will be implemented in our clinical practice immediately. Furthermore, this innovation will facilitate widespread clinical implementation of muscle ultrasound.

Methods

To be able to train and evaluate machine learning methods for the screening task, labeled data is required. To validate the transfer between different devices, the data should be from at least two different devices. No large dataset of a heterogenouos clinical population of suspected NMD cases had previously been made available to research, so we first processed all records from clinical practice since muscular ultrasound was introduced at the department in 2007. After filtering and retrieval of patient diagnosis from a separate database, we obtained two datasets, one with patients recorded on an older Philips iU22 device and the other from a newer ESAOTE 6100 machine. The number of patients as well as the data split are listed in the table.

| Philips iU22 | ESAOTE 6100 | |

|---|---|---|

| Training set | 644 | 794 |

| Validation set | 100 | 100 |

| Test set | 120 | 230 |

Number of patients in the splits of the two datasets collected for this project

Each patient record consists of a number of ultrasound images of different muscles and one binary diagnosis (i.e. NMD or no NMD). This allows us the formulate the screening task as follows: Given the set of images, does the patient suffer from neuromuscular disease?

We hypothesize that deep learning could be beneficial for the transfer between devices, automatically learning useful high level feature representations. Thus, we leverage pre-trained convolutional neural networks. Faced with the challenge of predicting labels for sets of images rather than just for individual images, we compare two methods for patient-level prediction, namely simple image aggregation and multi-instance learning.

Image aggregation

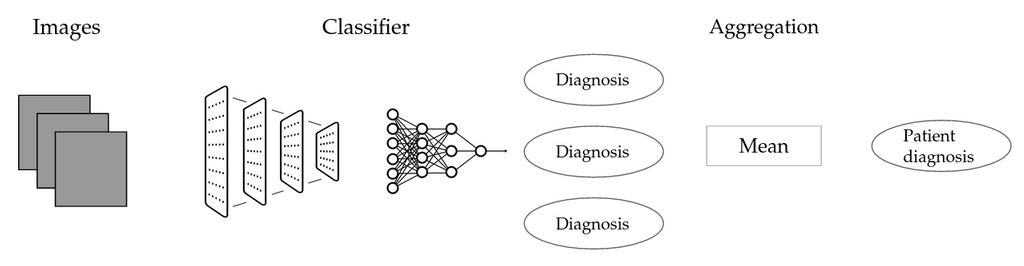

Schematic representation of the image aggregation method (IMG)

Schematic representation of the image aggregation method (IMG)

We do not have any information on whether an individual muscle is affected by a particular disease, rather, we only know the status of the patient at large. A simple workaround is to attribute the label of each patient to all associated images, to train an image-level classifier and then to aggregate image-level predictions. The first step is potentially problematic: No matter whether a given image shows a diseased muscle, it will be labeled as diseased if the patient is. Introducing label noise in this fashion could potentially render the image label classifier useless, thus also barring us from adequate patient level classification. \

Multi-instance learning

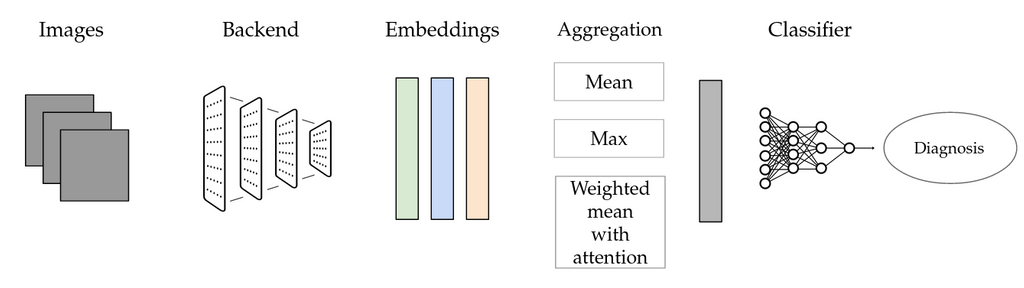

A possible alternative is Multi-instance learning (MIL). This technique can be suitable for scenarios with weak labels that do not apply to individual instances, but only to sets of instances, such as the current one. We use the following setup: Individual images are first fed through a neural network that serves as a backend. Activations from one of the layers of the network are then aggregated, using a so-called pooling layer. The pooled representation is finally classified by a separate neural network. This method allows to use bags of arbitrary size in a deep learning setting.

Schematic representation of multi-instance learning (MIL) as used for this project

Schematic representation of multi-instance learning (MIL) as used for this project

Traditional machine learning

It seems conceivable that the existing echogenicity features could be used even more effectively with a different classifier obtained via machine learning. Moreover, benchmarking only the rule-based system does not allow us to determine whether issues with generalization are inherent to the use of grayscale features, as they could also be due to the particular rules instead. For this reason, we devise two representations of patients that are then used for training a traditional machine learning model to predict patient diagnosis. The first condition (EIZ) is based on muscle-level z-scores that are already used in the rule-based method. For a given patient, we collect the distribution of the z-scores across muscles and sides. We represent the distribution with a small set of features. The second condition (EI) uses raw echogenicity values instead.

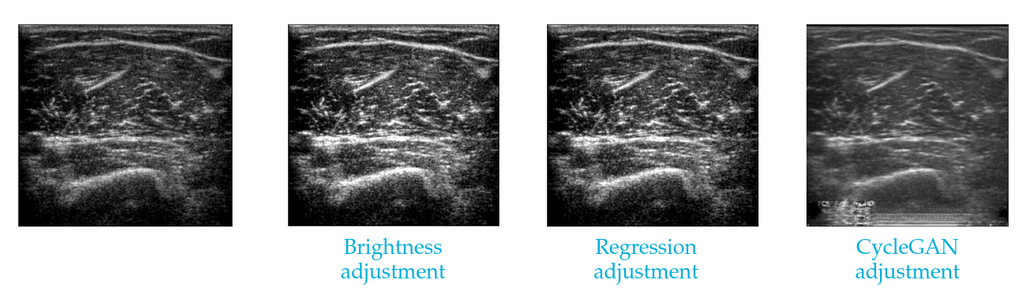

Domain adaptation

Various forms of unsupervised domain adaptation are investigated to ensure that a model trained on images from one ultrasound machine also works reliably on images from another machine. We experiment with domain-mapping methods: These are isolated fŕom the downstream task and map automatically map images from one domain to the other. We use two simple baselines: brightness adjustment uses the average image brightness on both datasets to make a simple correction and regression adjustment uses a small set of patients recorded on both devices to adjust the brightness. We also test one more involved method based on a CycleGAN (a deep learning method) for mapping the images.

An image from one ultrasound machine made to appear as if from another, using two simple brightness-based methods and a CycleGAN mapping.

An image from one ultrasound machine made to appear as if from another, using two simple brightness-based methods and a CycleGAN mapping.

Results

In this section, we first present a comparison of different methods when trained and evaluated on the same dataset. Afterwards, we look into the domain transfer scenario: The systems are trained on data from one device and then evaluated on the other.

In-domain performance

Here, we compare the rule-based system currently in clinical use to the two deep learning conditions and two additional baselines using traditional machine learning. The below table shows the area under the curve (AUC) of the different methods on the test set portion of the Esoate dataset. It can be seen that all methods are relatively similar. The second column shows no proposed methods have statistically significantly higher AUC. However, at the best performance point, all proposed methods offer a specificity-sensitivity tradeoff that is more geared towards sensitivity, which is desirable in the clinical scenario.

| AUC | p | Sn | Sp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rule-based | 0.765 | - | 0.624 | 0.885 |

| EI ML | 0.786 | 1 | 0.803 | 0.672 |

| EIZ ML | 0.786 | 1 | 0.779 | 0.719 |

| IMG | 0.783 | 1 | 0.777 | 0.717 |

| MIL | 0.750 | 1 | 0.795 | 0.681 |

In-domain performance comparison on Esaote test set. The table shows the area-under-the-curve (AUC) and the statistical significance of the difference in AUC to the baseline (p). Sensitivity (Sn) and Specificity (Sp) at best point, using Youden's method.

The below table shows the resuts of same evaluation protocol on the test set portion of the Philips dataset. Here, we can see statistically significant gains in AUC by the image aggregation deep learning condition, with an improvement of 10 percentage points. It also offers improvements in specificity and sensitivity.

| AUC | p | Sn | Sp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rule-based | 0.684 | - | 0.629 | 0.707 |

| EI ML | 0.762 | 0.09 | 0.611 | 0.862 |

| EIZ ML | 0.659 | 0.52 | 0.580 | 0.724 |

| IMG | 0.787 | 0.04 | 0.693 | 0.793 |

| MIL | 0.747 | 0.28 | 0.645 | 0.793 |

In-domain performance comparison on Philips test set.

Transfer between machines

In this section, we investigate the interaction of different classifiers and image mapping methods. We first train systems on the Esaote set and then adjust test set Philips image using the different mapping methods, the results are presented in the first table. Below, we reverse the process, training on Philips and deploying to Esaote.

| None | B | R | C | In-domain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rule-based | 0.5 | 0.67 | 0.727 | 0.696 | 0.684 |

| EI ML | 0.719 | 0.79 | 0.784 | 0.726 | 0.762 |

| EIZ ML | 0.606 | 0.716 | 0.771 | 0.783 | 0.659 |

| IMG | 0.504 | 0.632 | 0.661 | 0.413 | 0.787 |

| MIL | 0.415 | 0.769 | 0.719 | 0.379 | 0.747 |

Esaote to Philips transfer. AUC on Philips test set. Image mapping methods: B: Brightness, R: Regression, C: CycleGAN.

We can see that explicit methods for domain adaptation are necessary for the task: All classifiers suffer when used without adaptation methods. As already known informally beforehand, the rule-based method breaks down completely, performing only at chance level. Comparing it to the machine learning conditions, we can see that this effect seems to be mostly due to the particular rules, as these perform less badly when transformed, indicating that the grayscale features themselves can still be informative. We hypothesized that the neural methods would do better when tranferred between domains naively, but in fact they perform worse.

Comparing different mapping methods on the first shift, we can see that the very simple brightness-based mapping boosts performance throughout the board, though it is generally not quite on par with the models trained on the target domain. Regression-based mapping is better, delivering bigger gains and target-level performance for all but two classifiers. The CycleGAN is a good option when combined with non-neural methods, though the combination with neural methods performs much worse.

| None | B | R | C | In-domain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rule-based | - | - | - | - | 0.765 |

| EI ML | 0.581 | 0.68 | 0.708 | 0.691 | 0.786 |

| EIZ ML | - | - | - | - | 0.786 |

| IMG | 0.591 | 0.486 | 0.549 | 0.657 | 0.783 |

| MIL | 0.646 | 0.701 | 0.703 | 0.705 | 0.750 |

Philips to Esaote transfer. AUC on Esaote test set. Some conditions not available due to missing reference model.

For the opposite domain shift, we can see that all methods suffer from the shift between domains, though on this dataset, the neural methods do less so. The two methods that only adjust the brightness (B and R) works less well for neural methods on this domain, instead actually worsening performance for all conditions but MIL. The picture is the same for regression-based mapping. CycleGAN mapping works much better than for the opposite domain shift, increasing AUC for all methods. The reason for this difference might be that mapping images from Esaote to Philips is an easier task, as it involves more the destruction of details than their creation, as the Philips machine is older and offers a poorer resolution. For this reason, there might not be the issue with artifacts that affected the performance on the neural methods on the opposite shift.

Conclusion

In this study, we were interested in leveraging deep learning to improve the diagnostic accuracy of NMD screening with ultrasound imagery and to develop a system that does not require manual image annotation and transfers more easily between different devices than the current rule-based system. While we cannot show substantial improvements in classification performance across the board, the results presented are still encouraging: Deep learning is generally suitable for neuromuscular disease screening, achieving classification performance on par with the rule-based system currently in clinical use on one dataset and outperforming it on the other. Its use could eliminate the need for manual ROI annotation, as it is fully end-to-end.

Used in isolation, deep learning did however not alleviate the problem with the domain shift. We investigated different methods for domain adaptation between different devices and showed that simple baselines such as brightness-based alignment can already go a long way to improve performance. The more involved deep-learning based CycleGAN method was less unambiguously useful, especially when mapping images from a lower quality domain to a higher quality domain. The refinement of the method with a semantic consistency loss can be expected to alleviate this issue. There is a very large body of work on domain adaptation, so additional methods should also be experimented with. For current purposes, the simple mapping methods should be preferred. When matched images from both devices are available, the regression-based method can be used, but even if this is not the case, brightness-based mapping works surprisingly well.

In sum, we have demonstrated the viability of deep learning for the neuromuscular screening task and shown that domain adaptation can work to alleviate the problem associated with using a new machine. Further research should focus both on further improving the performance of the method and on the clinical use case of the method, investigating how doctors use the new system in a user user study.

Code and report

The code for this project can be found in this GitHub repository.

The final report for this project can be found here.